Now and then, you get glimpses of Old New England. Not the chic galleries and pride flags along Commercial Street in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Not the farm-to-table fine dining with views of the coast. Not Boston and its history of Irish immigration. You get it walking on the beach on a windy day when no one is around, those windswept sand dunes undulating like the sea before a storm, and you start to picture what the Pilgrims saw when they landed in Provincetown in 1620. This fact gets lost in our Thanksgiving story—we Americans are so gifted at myth-making—but on November 11, 1620, the Pilgrims came ashore on what is now one of the most LGBTQ-friendly, art-loving communities in America. They deemed the sandy shores too difficult for farming so they explored further inland, looking for a good spot to till and hoe. Five weeks later, they made their way to what is now called Plymouth, Massachusetts, naming the location after the port from which they had sailed.

We spent last weekend in Cape Cod. It had been two years since our last visit. Haunting seems like an appropriate, yet overused word to describe the area. Cape Cod—and New England—is a region, but also a mood. Every time I’m there, I think of hardship and resilience, isolation and community, beauty and danger. A trite phrase often used in travel writing is to describe a destination as a “place of contrasts,” which you could say about almost anywhere. Cape Cod—and, really all of New England—is a study in cyclical conflict, made all the more poignant by its four very distinct seasons. Winters are exceptionally cold, brutal and long. By April, the land and sky soften and you feel yourself willing to forgive. By August, you sit on the beach enjoying a lobster roll picnic, and you can’t remember winter’s fury. In October, when the leaves turn, when the pumpkins are everywhere, when the air shifts, you know you’re in the most beautiful place on Earth, yet you start to wonder what the darker months ahead will bring, and if you’ll be prepared.

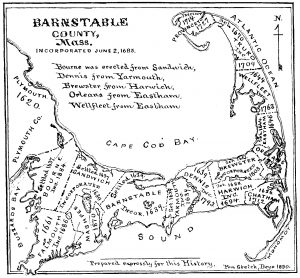

Cape Cod reaches about 65 miles into the Atlantic Ocean. On a map, it literally looks like a flexed arm putting its fist up to the Atlantic’s many storms, protecting the rest of Massachusetts. I walked out on part of that flexed arm last weekend; a sign warned me about sharks and to stay away from seals, which get eaten by sharks. Looking out to the sea, you felt Cape Cod protecting you from all that happens in the ocean. Go past that barrier at your own risk; for centuries, this stretch has been dubbed an “ocean graveyard.” The National Park Service reports there are one thousand shipwrecks between Wellfleet and Truro, which is less than five miles long. The first recorded shipwreck occurred six years after the Pilgrims landed. Winter months, not surprisingly, were the worst, with an estimated two wrecks every month during the early 1800s. The region gets pounded by storms, blizzards, hurricanes. A category 3 hurricane hit the area in 1635, a force of nature settlers born in Europe had never heard of or seen before. The beaches, no doubt, could tell us many, many stories, everything from who showed up and when, to the horror unspooling in the waves, to the objects fishermen accidentally reeled in, to children scampering about getting a sunburn. The beaches have seen it all.

When I think about leaving the Northeast, I think about escaping New York City, but when I think about leaving New England, I hesitate. Jobs brought and kept us here, in New York, but New England pulls us away from all that. I grew up vacationing in Mystic, Connecticut. As a child, I remember being fearful of all those oil paintings featuring angry sperm whales attacking sailors. I got married in Vermont on the coast of Lake Champlain. My first newspaper job was in Dover, New Hampshire, the Granite State’s “Seacoast,” a 40-mile stretch of oceanfront. On my days off, I used to sit and chill on the sand in York, Maine, another beach that has seen its own share of shipwrecks. In fact, in 2013, a storm washed away enough sand to reveal the bones of sloop dating between 1750 and 1850.

Today, back in suburban New Jersey, I miss coastal New England. The gray weather here doesn’t feel intriguing like the gray weather there. Last weekend, on an overcast rainy day, I visited the Provincetown Library, an impressive building given to the town in 1873. The first thing I saw walking in was its “Mysteries” section. New Englanders love their spooky yarns. Stephen King is a lifelong Maine resident. Before King, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts,—witch trial central—was writing about all the shit in the woods that could kill you, or, at the very least, emotionally scar you for life. Somehow, when you drive west and cross the Connecticut border back into New York and turn south to head into New Jersey, New England’s haunting beauty dissipates. It’s not going to compete with malls or the Manhattan skyline or traffic. You have to go there to feel it.

We rented a condo in Provincetown, just two blocks from Commercial Street and all its wonderful restaurants and galleries, and every morning as I poured myself a cup of coffee, I would look out from the kitchen and see the Provincetown Cemetery, a few of the taller headstones poking up from a hill. There are stones dating to the early 1800s, also worn by Cape Cod’s mercurial weather. If you read the dates on many of these graves, you realize a number of people barely made it to age 45. Many graves lack a birth date because the information wasn’t available.

And that’s Cape Cod, and much of New England right now: orange and brown leaves blowing past old headstones; people curling up indoors reading a good mystery; waves and winds hitting the beaches harder; fireplaces going strong inside restaurants serving chowder because it’s getting cold and warming up takes more effort. And it’s all beautiful, even when it feels creepy.